“The opportunity for every child to learn and to make the most of their talents is at the heart of a fairer society. Yet in country after country it is wealth, not talent, that dictates a child’s educational destiny.… This reality is failing individual children, each of whom has a right to education. It is also failing society, as a generation of talented poor girls and boys cannot fulfil their promise and contribute fully to human progress. Brilliant doctors, teachers or entrepreneurs are instead herding goats or collecting water. Humanity faces unprecedented challenges. Yet instead of utilizing the talents of all of people, inequality means we are squandering this potential.”

Understanding the Numbers: Good News and Bad

More people in the world today are educated than ever before. In 1820 only 12% of the people in the world could read and write. Today the share is reversed: only 17% of the world’s population remains illiterate. Primary school enrollment is now almost universal in most countries, with as many girls enrolling as boys.

Nevertheless, these figures overshadow the impact of persistent inequity. Some 63 million children of primary school age were out of school in 2016 and progress on primary school enrollment remains flat. Most impacted are the world’s poorest countries, where the lack of basic education is a hard constraint on development. In Niger, for example, just 36.5% of 15- to 20-year-olds are literate.

A small village private school in Dasdoi, Uttar Pradesh, India

Oxfam caught the world’s attention in 2014 with the astounding statistic that just 85 individuals had the same wealth as the 3.8 billion people who make up the poorest half of the world’s population. Three years later the number was down to 43, and in 2018 to just 26. In their annual report to the 2019 World Economic Forum in Davos, Public Good or Private Wealth, Oxfam takes a strong, unequivocal position: this spiraling inequity must be checked, and the way to do it is for all governments to provide universal health care, education and social protection, free at the point of delivery, funded by fair taxation of rich individuals and corporations. Governments, says Oxfam, must “Stop supporting privatization of public services.”

“For some time, the view of institutions like the World Bank was that public services should be rationed and minimal, and that the private sector is often a better provider. It was argued that individuals should pay for their schools and hospitals, market mechanisms should be used to organize services, and that social protection should be very limited and targeted only at the very poorest people. While some of the rhetoric, programming and advice has changed, including notably from the IMF, change in practice has been slower. This trend is too often compounded by the influence of elites over politics and governments, skewing public spending in the wrong direction and ensuring that it benefits the already wealthy rather than those who need it most. It is time to focus on what works. To most effectively reduce the gap between rich and poor, public services need to be universal, free, public, accountable and to work for women…

“The World Bank and some donor governments are upbeat about the possibility of public-private partnerships (PPPs) and private provision as alternatives to government-funded services. Yet research by Oxfam and other NGOs has shown clearly that education, health and other public services delivered privately and funded through PPPs are not a viable alternative to government delivery of services. Instead they can drive up inequality and drain government revenues. Even the IMF is now warning of the sizeable fiscal risks of pursuing PPP approaches.”

In Pakistan a large majority of the schools enroll more boys than girls, and drop-out rates for girls are reportedly higher. Photo by Vicki Francis/Department for International Development.

Pakistan, for example, has 24 million children out of school, with just 15% of poor rural girls finishing primary school. Public spending on education is among the lowest in the world. The state of Punjab is no longer building new public schools and instead, turning over management of the public schools to the private sector. The goal was to get more of the 5.5 million out-of-school children in Punjab into school, but Oxfam’s research shows this is not what’s happening. Only 1.3% of children in the schools surveyed had previously been out of school. A large majority of the schools enrolled more boys than girls, and drop-out rates for girls were reported to be higher. Non-fee expenditures like uniforms can be as much as 40% of the household income of the poorest households, so many families choose to educate only their male children. One private school principal is quoted as saying, “We as school owners cannot include the poorest of the poor in this school with other kids. It’s not like a charity; we have limited funds from the PPP, and I also need to earn a livelihood from this.” Teachers in the PPP, mostly women, are poorly paid and this further exploits gender inequality.

On the other hand, there are many examples of developing countries successfully expanding access by providing universal free education:

- In Uganda, removing direct costs through universal primary education increased enrollment by over 60 percent and significantly lowered cost-related dropouts.

- In Malawi, free primary education increased enrollment by half, favoring girls and poor people.

- In Ghana, in September 2017, after fees for senior high (upper secondary) school were dropped, 90,000 more students walked through the school doors at the start of the new academic year.

- Sierra Leone’s government has made primary and secondary education free and is increasing tax collection from the richest.

- Ethiopia is a poor country, with around the same per capita income as Canada’s in 1840. And yet it is the fifth-largest spender on education in the world as a proportion of its budget, employing over 400,000 primary school teachers. Between 2005 and 2015, it brought 15 million more children into school. Ethiopia still faces serious challenges with learning outcomes and improving the quality of education, but as Oxfam reports, “the scale of its commitment and effort to educate its girls and boys is dramatic.”

Education for All—Starting with Women

Achieving greater equality between women and men and increased empowerment of women and girls has long been recognized as a global imperative for development. In 2015 it was made a stand-alone goal in the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDG5).

Goal #5 of The Global Resolutions Initiative: “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.” 2018 progress update.

Education is key to meeting that goal, and there has been real progress. Globally, 90% of girls now complete primary school, but only 75% complete their lower secondary education. In low income countries, the situation is less encouraging: fewer than 67% of girls complete their primary education, and only 33% completes lower secondary school. Income and gender combine for a crushing result. According to Oxfam, in Kenya, a girl from a poor family has a one in 250 chance of pursuing her studies beyond secondary school, compared to a one in three chance for a boy from a rich family.

A 2019 OECD global report points out that “Despite increasing investment in efforts to reduce gender gaps and empower women over the last 25 years, at the current rate of progress it will still require over 200 years to achieve SDG 5, which is the equivalent to nine generations.”With even a few years of primary education, women’s economic prospects improve; they have fewer and healthier children, and better chances of sending their children to school.

The World Bank calculates that this failure to educate girls costs the world economy as much as $30 trillion in lost earnings and productivity. It also comes at a high cost to their health and well-being. Globally, women with secondary education earn twice as much as women with no education. Education not only narrows the pay gap with men, it also increases their self-confidence and decision-making power in the household. Women typically invest a higher proportion of their earnings in their families and communities than do men. With even a few years of primary education, women’s economic prospects improve; they have fewer and healthier children, and better chances of sending their children to school. UNESCO estimates that if all girls were to receive a secondary education, there would be a 64% reduction in early and forced child marriages which greatly increase the risk of death in childbirth. If all girls completed even a primary education, an estimated 189,000 maternal deaths would be avoided annually – a reduction of two-thirds.

Regrettably, cultural norms and the misinterpretation of religious concepts have too often led to violence against women of all ages, and present a major deterrent to girls’ education. Honor killings, abduction, rape, and sexual harassment still occur with near impunity in too many countries. As the Oxfam report points out, public education can be truly transformative for girls and women when schools are used as spaces to challenge the attitudes of parents and communities that act as barriers to gender equality. But as evident from the Pakistan example, “school fees can stop children going to school, and especially girls. Women and girls lose out the most when fees are charged for public services: in many societies, their low social status and lack of control over finances means they are last in line to benefit from education or medical care.”

Schooling Is Not the Same as Learning

According to World Bank’s 2018 report, Learning to Realize Education’s Promise, the rise in school enrollment does not mean that all those children are getting a good education. Globally, 125 million children are not acquiring functional literacy or numeracy, even after four years in school. “Rabia Nura, a 16-year-old girl from Kano in northern Nigeria, goes to school despite ever-present threats from Boko Haram. She is determined to become a doctor. But 37 million African children will learn so little in school that they will not be much better off than kids who never attend school.”In low-income countries chronic malnutrition, disease, and chaotic or violent environments undermine children’s early development.

Poverty/inequity is certainly a factor, both between and within countries. In low-income countries, the average student performs worse than 95% of the students from wealthier OECD countries. In South Africa, third graders from the poorest households are three years behind those from the richest households.

Many factors compromise school effectiveness in low-income countries. Chronic malnutrition, disease, and chaotic or violent environments undermine children’s early development. High-quality teachers—in fact, all teachers—are in short supply. School management is often weak, and availability of resources can’t always keep pace with fast-rising enrollments.

But as both Oxfam and World Bank point out, lower learning levels are not an inevitable result of either rapidly expanding enrollment or poverty. South Korea and Vietnam are examples of countries that have achieved excellent across-the-board learning in the midst of rapid expansion. These countries, like all of the world’s best performing school systems, “manage to provide high-quality education to all students rather than only to students from privileged groups.” Good schools make a big difference.

What Should the Poor Expect from Education?

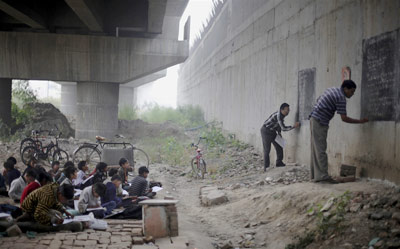

Indian children attend a school run under a bridge in India.

The poor in the developing world and those stranded in refugee camps across the world know what they want for their children. Almost all of them recognize that a good education is key to providing a better future for their children and improving their own quality of life.

First and foremost, education needs to prepare young people so that they and their community can get out of poverty. Education in all communities, especially in the developing world, needs to involve parents, students, and teachers and address the needs of the local community first, and then society at large. The subjects taught would then be relevant to learners. It’s not as if children lack the potential to change their world for the better. They are, as it were, waiting for the opportunities to expand their natural ability to create, learn and problem solve.

In Redefining Education in the Developing World, Marc J. Epstein and Kristi Yuthas contend that the very idea of what constitutes quality education for students in the developing world must change. Government agencies and other organizations, they say, should shift the focus from test scores and mastery of traditional curriculum to helping students develop knowledge and skills that are relevant to their lives and can lift them and their communities out of poverty. It’s time, they write, “to seek out the interventions that lead to the greatest social and economic impact for the poor.”

Tanzania, for example, has a high number of unemployed graduates who attained good degrees that have no or little application in their local communities. They may well have been excellent pupils, but were not taught to think critically, problem-solve, or focus on studies that would lead to a better livelihood either for themselves or their communities.

As the World Bank report puts it “Having knowledge is not the same as being able to apply it. Having a skill means having the ability to do something well. Having a skill requires knowledge, but having knowledge does not necessarily imply having skills. Knowing how a wind turbine works does not mean a person has the skill to fix one.”

Epstein and Yuthas advocate a concept they call “school of life”: “Conceptual knowledge is put into practice at school through activities that empower children to use what they have learned. For example, students practice routine health behaviors, such as hand washing and wearing shoes near latrines—and, to the extent feasible, gain exposure to other important behaviors, such as boiling drinking water and using malaria nets. …

Fundación Escuela Nueva is changing the way children learn from Colombia to Southeast Asia.

“Students also develop higher order skills as they work in committees to develop and execute complex projects. Health-related projects can range from planning and carrying out an athletic activity to be played during recess, to practicing diagnostic skills when classmates are ill—helping to decide, for example, when a cold has turned into a respiratory infection that requires antibiotics. Entrepreneurship projects include identifying and exploiting market opportunities through business ideas like school gardens or community recycling that create real value. Students learn and practice workplace skills and attitudes like delegation, negotiation, collaboration, and planning—opportunities that are rarely available to them outside their families.”

Schools, they say, should “adopt action-oriented pedagogical approaches that hone critical thinking skills and enable children to identify problems, seek out and evaluate relevant information and resources, and design and carry out plans for solving these problems. This involves tackling real problems that require and empower students to take the initiative and responsibility for their own learning.”

Are Technology-Driven Solutions Applicable?

Children from New Delhi search for answers in a Self Organized Learning Environment classroom.

Charles Kenny, senior fellow at the Centre for Global Development, observed: “Technology has become one of the greatest vehicles for change. … Young people are natural adopters of new technologies and certainly the potential for technology and digital media to be a force for innovation, education and change is just beginning to be realised.”“Young people are natural adopters of new technologies and certainly the potential for technology and digital media to be a force for innovation, education and change is just beginning to be realised.”

The internet provides a unique opportunity for people everywhere to learn about themselves and their world. Today any literate person can ask any question, research any topic, check and analyze it, and come up with an in-depth understanding within weeks—something that, prior to this period in our history, would have taken months, even years. The internet also opens up possibilities for young people to connect as problem-solvers and participants in our global community.

Experiments with tablets and laptops have had limited success, unless the intervention is guided by national, cultural and social considerations, and adapted to the local communities’ unique needs and the task to be accomplished. Developers and content providers need a real understanding of the people who will be using the devices: who they are, where they are, and what they need to learn. As Epstein and Yuthas noted, students in poor areas of developing countries may first and foremost need to learn life skills that enable them to improve their financial prospects and well-being. These might include financial literacy and entrepreneurial skills, health maintenance and management, and administrative capabilities such as teamwork, problem solving, and project management.

Teachers who have grown up with limited access to technology need training and professional development opportunities that are of sufficient duration and detail so they can understand and use educational technology resources for their learners. Studies show that the tendency to provide minimal training within a short time period does not work. This is a problem, because so many teachers in developing countries are both under-qualified and underpaid. One solution might be to “train the trainers”— select the very best and train them sufficiently well to train others in their location.

Children use Sugata Mitra’s hole-in-the-wall computer in a slum in New Delhi. Credit: TED/Sugata Mitra.

Teacher shortage in general is a pressing issue for developing countries. According to UNESCO, the world needs another 69 million teachers to deliver education for all. Technology is sometimes considered as a way to compensate for the lack teachers. In response to teacher shortages, Sugata Mitra initiated his famous “hole-in-the wall” experiments and “Granny Cloud” programs that focus on students using computers to drive their own learning. The role of teachers is to pose big questions, and the Grannies to provide enthusiastic support and encouragement.

Bridge schools, the controversial chain of low-fee, for-profit schools operating in Africa and India, uses technology in a different way. Pre-scripted lesson plans are written remotely, often in the US, and transmitted to e-readers in the hands of instructors who are not usually certified teachers, and who are not posing or encouraging questions.

Writes New York Times reporter Peg Tyre, “in some of the 20 or so Bridge classrooms I observed, pupils occasionally asked questions, but Bridge instructors ignored them. Teachers say that they are required to read the day’s script as written or risk a reprimand or eventual termination, and they do not have time to entertain questions.” The intentions may be good, but results of these schools are not clear. Most concerning, says education professor Prachi Srivastava, is that “Impacts on higher order skills, like creativity and critical thinking, are not known.”

Another issue with educational technology in the developing world is that many schools still do not have reliable electricity or broadband access, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Many lack basic supplies like books, writing materials, and even a place to sit or a surface to write on. The widespread use of mobile devices and smartphones is improving access, though growth in Africa has slowed.Mobile reading, opens up new pathways to literacy for marginalized groups, particularly women and girls.

Donald Clark, founder of the e-learning company Epic Group, believes that learning with mobile technology is producing a “renaissance of reading and writing” among young people across the world, and is the “single most important factor in increasing literacy on the planet. Why? Every child is massively motivated to learn to text, post and message. The evidence shows that they become obsessive readers and writers through mobile devices,” he says. “Texting is a significant form of literacy, introduced by youngsters, on their own, spontaneously, rapidly and without tuition.”

A 2014 UNESCO study, Reading in the Mobile Era, found that mobile reading, or m-learning, opens up new pathways to literacy for marginalized groups, particularly women and girls and others who may not have access to paper books. People use mobile devices to read to children, supporting literacy and other forms of learning, and seem to enjoy reading more and read more often.

Providing literacy, numeracy, other educational programs and books to underserved communities via mobile devices is a natural solution through which communities can begin to leapfrog traditional twentieth century educational methodologies. The price of a mobile book can be 300 times cheaper than obtaining a physical text.

Simple and common Nokia phones are found even in remote villages of Afghanistan. Software called “Ustad Mobile” utilizes these more affordable cell phones as teaching tools.

UNESCO’s findings indicate that women and girls tend to use mobile devices for reading and learning more than do their male counterparts, but have less access to these devices than men. Since about two out of every three illiterate people are female, an urgent solution is to ensure women have equal access to mobile phones. There may well be cultural resistance to this in some countries. And unfortunately, governments are as yet not taking enough advantage of m-learning. More work needs to be done to promote this as a cost-effective way to improve education for men and women of all ages, and to improve infrastructure and guarantee reliable broadband connectivity.

Many programs around the world are tackling the challenges of expanding meaningful education in the developing world, both public and private.

- BRAC, a Bangladesh NGO dedicated to alleviating poverty by empowering the poor, owns and operates 32,000 primary schools operating in 12 countries.

- Pratham provides literacy and other educational support programs, and has served some 33 million children in India. Google has been funding Pratham through Storyweaver, an open source platform to share and translate books. As many as 30 languages are spoken in India. Now with books in 60 languages and the ability to post new stories, the platform integrates Google Translate, transliteration tools, and Google volunteers to improve the translation. The goal is to provide 200,000 titles for 500,000 users.

- Escuela Nueva, originating in Columbia, is an educational model for collaborative learning. Students work in small groups, using interactive modules designed to promote dialogue, critical thinking, and the application of new knowledge to family and community situations.

- Savelugu Girls Model School in northern Ghana, is one of dozens of model schools in the north of the country funded and administered by the local authorities. According to Oxfam, who partnered with Ghana Education Service, the school district, and local communities to build the school, “Teaching is based on learner-centered methodologies, a concept that has previously not applied very often by teachers in this part of Ghana, who lacked the know-how to implement it. Discussions and group work are core elements. The girls form study groups in the evenings. Parents are invited to support the girls’ education through school management committees. Computers are integrated into lessons, and teachers are trained to encourage the girls to participate actively in the classroom, and even to challenge teachers with individual points of view. These schools go beyond the national curriculum to address sexual health and life skills.”

- Future Prowess Foundation School in Maiduguri, Nigeria, incorporates Islamic education with Western education and vocational training. The school takes in children of Boko Haram fighters as well as those whose parents were killed by the fighters; the children of security forces attend, as do the children of traditional rulers and religious leaders. “Bringing them all to learn under the same roof promotes friendly co-existence among the children thereby building everlasting peace,” says Suleiman Aliyu, the head teacher.

Corporations are also engaged, particularly in providing technology.

- In 2016 Google launched a $50 million global program to support organizations that are using technology to help children who do not have basic math and reading skills, even after several years of school.

- Google’s Rumie educational tablet, targeted to older kids who can already read, is essentially a “library on a chip.” It is low-cost, lightweight, updatable, trackable, and does not depend on an internet connection. Content can be adapted to age and learning level, tailored to local context, and continually updated.

- Worldreader uses technology to deliver books and other content, working with a variety of governments, nonprofits, local agencies, and corporations, notably Amazon. Worldreader has distributed about 25,000 preloaded Kindles to 160,000 people in 12 sub-Saharan African countries. Says David Risher, founder of Worldreader, “It really is the best way to get books into people’s hands where the physical infrastructure isn’t very good, the roads are bad, gas costs too much . . . but you can beam books through the cellphone network just like you can make a phone call—and that’s really the thing that changes kids’ lives.” The e-readers contained culturally and age appropriate reading materials in both local language and English.

Refugees: A Growing Crisis

According to the 2019 UNESCO Global Education Monitoring (GEM) report, Migration, Displacement and Education: Build Bridges Not Walls, there are in the world today more than 25 million refugees and nearly 60 million people internally displaced by war and natural disasters. More than half of refugees are under age 18, and 1 in 6 are under age 5. The school-age children in these populations could fill half a million classrooms. Clearly, the UN’s landmark 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants call for all refugee and migrant children to be receiving education within a few months of arrival is not being met.

In the world today there are more than 25 million refugees and nearly 60 million people internally displaced by war and natural disasters. Photo: Democratic Republic of the Congo, by Julien Harneis.

The GEM report emphasizes that guaranteeing the right of migrant and refugee children to quality education